1. Import Python libraries¶

A honey bee.

A honey bee.

The question at hand is: can a machine identify a bee as a honey bee or a bumble bee? These bees have different behaviors and appearances, but given the variety of backgrounds, positions, and image resolutions it can be a challenge for machines to tell them apart.

Being able to identify bee species from images is a task that ultimately would allow researchers to more quickly and effectively collect field data. Pollinating bees have critical roles in both ecology and agriculture, and diseases like colony collapse disorder threaten these species. Identifying different species of bees in the wild means that we can better understand the prevalence and growth of these important insects.

A bumble bee.

A bumble bee.

This notebook walks through loading and processing images. After loading and processing these images, they will be ready for building models that can automatically detect honeybees and bumblebees.

# Used to change filepaths

from pathlib import Path

# We set up matplotlib, pandas, and the display function

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from IPython.display import display

import pandas as pd

# import numpy to use in this cell

import numpy as np

# import Image from PIL so we can use it later

from PIL import Image

# generate test_data

test_data = np.random.beta(1,1,(100,100,3))

# display the test_data

plt.imshow(test_data)

%%nose

import matplotlib as mpl

def test_task1_0():

assert (test_data.shape == (100, 100, 3)), \

'The test_data you created is not the right shape! It should be 100, 100, 3'

def test_task_1():

assert '_' in globals() and isinstance(globals()['_'], mpl.image.AxesImage), \

'Did you forget to call `plt.imshow` on your test data?'

def test_task_2():

assert 'Image' in globals(), \

'Did you forget to import `Image` from `PIL`?'

2. Opening images with PIL¶

Now that we have all of our imports ready, it is time to work with some real images.

Pillow is a very flexible image loading and manipulation library. It works with many different image formats, for example, .png, .jpg, .gif and more. For most image data, one can work with images using the Pillow library (which is imported as PIL).

Now we want to load an image, display it in the notebook, and print out the dimensions of the image. By dimensions, we mean the width of the image and the height of the image. These are measured in pixels. The documentation for Image in Pillow gives a comprehensive view of what this object can do.

# open the image

img = Image.open('datasets/bee_1.jpg')

# Get the image size

img_size = img.size

print("The image size is: {}".format(img_size))

# Just having the image as the last line in the cell will display it in the notebook

img

%%nose

import PIL

def test_task2_0():

assert 'img' in globals() and isinstance(img, PIL.JpegImagePlugin.JpegImageFile), \

'Did you load the image using the `open` method and assign it to `img`?'

def test_task2_1():

assert (img_size == (100, 100)), \

'Did you get the size from the image! It should be 100, 100'

3. Image manipulation with PIL¶

Pillow has a number of common image manipulation tasks built into the library. For example, one may want to resize an image so that the file size is smaller. Or, perhaps, convert an image to black-and-white instead of color. Operations that Pillow provides include:

- resizing

- cropping

- rotating

- flipping

- converting to greyscale (or other color modes)

Often, these kinds of manipulations are part of the pipeline for turning a small number of images into more images to create training data for machine learning algorithms. This technique is called data augmentation, and it is a common technique for image classification.

We'll try a couple of these operations and look at the results.

# Crop the image to 25, 25, 75, 75

img_cropped =img.crop(box=(25, 25, 75, 75))

display(img_cropped)

# rotate the image by 45 degrees

img_rotated = img.rotate(45)

display(img_rotated)

# flip the image left to right

img_flipped = img.transpose(method=Image.FLIP_LEFT_RIGHT)

display(img_flipped)

%%nose

def test_task3_0():

assert img_cropped.size == (50, 50), \

'Did you crop `img` using the .crop() method?'

def test_task3_1():

# top left pixel will be black

assert (np.array(img_rotated)[0, 0, :] == 0).all(), \

'Did you rotate `img` 45 degrees using the .rotate() method?'

def test_task3_2():

# check the first column in the image is now the last

assert (np.array(img)[:, 0, :] == np.array(img_flipped)[:, -1, :]).all(), \

'Did you flip `img` using the .transpose() method?'

4. Images as arrays of data¶

What is an image? So far, PIL has handled loading images and displaying them. However, if we're going to use images as data, we need to understand what that data looks like.

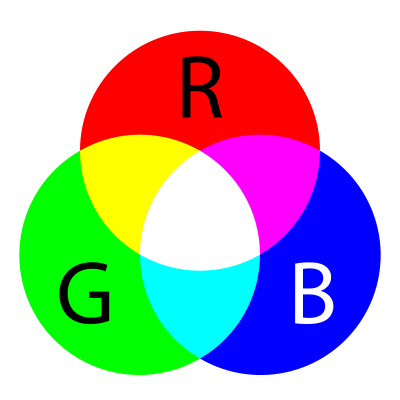

Most image formats have three color "channels": red, green, and blue (some images also have a fourth channel called "alpha" that controls transparency). For each pixel in an image, there is a value for every channel.

The way this is represented as data is as a three-dimensional matrix. The width of the matrix is the width of the image, the height of the matrix is the height of the image, and the depth of the matrix is the number of channels. So, as we saw, the height and width of our image are both 100 pixels. This means that the underlying data is a matrix with the dimensions 100x100x3.

# Turn our image object into a NumPy array

img_data = np.array(img)

# get the shape of the resulting array

img_data_shape = img_data.shape

print("Our NumPy array has the shape: {}".format(img_data_shape))

# plot the data with `imshow`

plt.imshow(img_data)

plt.show()

# plot the red channel

plt.imshow(img_data, cmap=plt.cm.Reds_r)

plt.show()

# plot the green channel

plt.imshow(img_data ,cmap=plt.cm.Greens_r)

plt.show()

# plot the blue channel

plt.imshow(img_data, cmap=plt.cm.Blues_r)

plt.show()

%%nose

import PIL

def test_task4_0():

assert img_data_shape == (100, 100, 3), \

'Did you convert `img` to an array with `np.array` and then get the shape with `.shape`?'

5. Explore the color channels¶

Color channels can help provide more information about an image. A picture of the ocean will be more blue, whereas a picture of a field will be more green. This kind of information can be useful when building models or examining the differences between images.

We'll look at the kernel density estimate for each of the color channels on the same plot so that we can understand how they differ.

When we make this plot, we'll see that a shape that appears further to the right means more of that color, whereas further to the left means less of that color.

def plot_kde(channel, color):

""" Plots a kernel density estimate for the given data.

`channel` must be a 2d array

`color` must be a color string, e.g. 'r', 'g', or 'b'

"""

data = channel.flatten()

return pd.Series(data).plot.density(c=color)

# create the list of channels

channels = ['r','g','b']

def plot_rgb(image_data):

# use enumerate to loop over colors and indexes

for ix, color in enumerate(channels):

plot_kde(image_data[:,:,ix], color)

plt.show()

plot_rgb(img_data)

%%nose

def test_task5_0():

assert channels == ['r', 'g', 'b'], \

'Did you setup the `channels` variable properly?'

6. Honey bees and bumble bees (i)¶

Now we'll look at two different images and some of the differences between them. The first image is of a honey bee, and the second image is of a bumble bee.

First, let's look at the honey bee.

# load bee_12.jpg as honey

honey=Image.open('datasets/bee_12.jpg')

# display the honey bee image

display(honey)

# NumPy array of the honey bee image data

honey_data = np.array(honey)

# plot the rgb densities for the honey bee image

plot_rgb(honey_data)

%%nose

import PIL

def test_task6_0():

assert 'honey' in globals() and isinstance(honey, PIL.JpegImagePlugin.JpegImageFile), \

'Did you load `datasets/bee_12.jpg` using the `open` method and assign it to `honey`?'

def test_task6_1():

assert 'honey_data' in globals() and (honey_data == np.array(honey)).all(), \

'Did you create `honey_data` from `honey` with `np.array`?'

7. Honey bees and bumble bees (ii)¶

Now let's look at the bumble bee.

When one compares these images, it is clear how different the colors are. The honey bee image above, with a blue flower, has a strong peak on the right-hand side of the blue channel. The bumble bee image, which has a lot of yellow for the bee and the background, has almost perfect overlap between the red and green channels (which together make yellow).

# load bee_3.jpg as bumble

bumble=Image.open('datasets/bee_3.jpg')

# display the bumble bee image

display(bumble)

# NumPy array of the bumble bee image data

bumble_data = np.array(bumble)

# plot the rgb densities for the bumble bee image

plot_rgb(bumble_data )

%%nose

import PIL

def test_task7_0():

assert 'bumble' in globals() and isinstance(bumble, PIL.JpegImagePlugin.JpegImageFile), \

'Did you load `datasets/bee_3.jpg` using the `open` method and assign it to `bumble`?'

def test_task7_1():

assert 'bumble_data' in globals() and (bumble_data == np.array(bumble)).all(), \

'Did you create `bumble_data` from `bumble` with `np.array`?'

8. Simplify, simplify, simplify¶

While sometimes color information is useful, other times it can be distracting. In this examples where we are looking at bees, the bees themselves are very similar colors. On the other hand, the bees are often on top of different color flowers. We know that the colors of the flowers may be distracting from separating honey bees from bumble bees, so let's convert these images to black-and-white, or "grayscale."

Grayscale is just one of the modes that Pillow supports. Switching between modes is done with the .convert() method, which is passed a string for the new mode.

Because we change the number of color "channels," the shape of our array changes with this change. It also will be interesting to look at how the KDE of the grayscale version compares to the RGB version above.

# convert honey to grayscale

honey_bw = honey.convert('L')

display(honey_bw)

# convert the image to a NumPy array

honey_bw_arr = np.array(honey_bw)

# get the shape of the resulting array

honey_bw_arr_shape = honey_bw_arr.shape

print("Our NumPy array has the shape: {}".format(honey_bw_arr_shape))

# plot the array using matplotlib

plt.imshow(honey_bw_arr , cmap=plt.cm.gray)

plt.show()

# plot the kde of the new black and white array

plot_kde(honey_bw_arr, 'k')

%%nose

def test_task8_0():

assert honey_bw_arr.shape == (100, 100), \

'Did you convert `honey_bw` to an array with `np.array` and then get the shape with `.shape`?'

assert honey_bw_arr_shape == (100, 100), \

'Did you convert `honey_bw` to an array with `np.array` and then get the shape with `.shape`?'

9. Save your work!¶

We've been talking this whole time about making changes to images and the manipulations that might be useful as part of a machine learning pipeline. To use these images in the future, we'll have to save our work after we've made changes.

Now, we'll make a couple changes to the Image object from Pillow and save that. We'll flip the image left-to-right, just as we did with the color version. Then, we'll change the NumPy version of the data by clipping it. Using the np.maximum function, we can take any number in the array smaller than 100 and replace it with 100. Because this reduces the range of values, it will increase the contrast of the image. We'll then convert that back to an Image and save the result.

np.maximum(honey_bw_arr,100)

# flip the image left-right with transpose

honey_bw_flip = honey_bw.transpose(method=Image.FLIP_LEFT_RIGHT)

# show the flipped image

display(honey_bw_flip)

# save the flipped image

honey_bw_flip.save('saved_images/bw_flipped.jpg')

# create higher contrast by reducing range

honey_hc_arr = np.maximum(honey_bw_arr,100)

# show the higher contrast version

plt.imshow(honey_hc_arr, cmap=plt.cm.gray)

# convert the NumPy array of high contrast to an Image

honey_bw_hc = Image.fromarray(honey_hc_arr)

# save the high contrast version

honey_bw_hc.save('saved_images/bw_hc.jpg')

%%nose

import os

def test_task9_0():

assert 'honey_hc_arr' in globals() and (honey_hc_arr >= 100).all(), \

'Did you use np.maximum(honey_bw_arr, 100) to create a high contrast version?'

def test_task9_1():

assert 'honey_bw_flip' in globals() and (np.array(honey_bw_flip)[:, 0] == honey_bw_arr[:, -1]).all(), \

'Did you use np.maximum(honey_bw_arr, 100) to create a high contrast version?'

def test_task9_2():

assert os.path.exists("saved_images/bw_flipped.jpg"), \

'Did you save the flipped image with `honey_bw_flip.save`?'

def test_task9_3():

assert os.path.exists("saved_images/bw_hc.jpg"), \

'Did you save the high contrast image with `honey_bw_hc.save`?'

10. Make a pipeline¶

Now it's time to create an image processing pipeline. We have all the tools in our toolbox to load images, transform them, and save the results.

In this pipeline we will do the following:

- Load the image with

Image.openand create paths to save our images to - Convert the image to grayscale

- Save the grayscale image

- Rotate, crop, and zoom in on the image and save the new image

image_paths = ['datasets/bee_1.jpg', 'datasets/bee_12.jpg', 'datasets/bee_2.jpg', 'datasets/bee_3.jpg']

def process_image(path):

img = Image.open(path)

# create paths to save files to

bw_path = "saved_images/bw_{}.jpg".format(path.stem)

rcz_path = "saved_images/rcz_{}.jpg".format(path.stem)

print("Creating grayscale version of {} and saving to {}.".format(path, bw_path))

bw = img.convert('L')

bw.save(bw_path)

print("Creating rotated, cropped, and zoomed version of {} and saving to {}.".format(path, rcz_path))

rcz = bw.rotate(45).crop(box=(25, 25, 75, 75)).resize(size=(100,100))

rcz.save(rcz_path)

# for loop over image paths

for img_path in image_paths:

process_image(Path(img_path))

%%nose

import os

def test_task10_0():

image_paths = ['datasets/bee_1.jpg', 'datasets/bee_12.jpg', 'datasets/bee_2.jpg', 'datasets/bee_3.jpg']

for img in image_paths:

path = Path(img)

bw_path = "saved_images/bw_{}.jpg".format(path.stem)

rcz_path = "saved_images/rcz_{}.jpg".format(path.stem)

assert os.path.exists(bw_path), "Did you save the file {}?".format(bw_path)

assert os.path.exists(rcz_path), "Did you save the file {}?".format(rcz_path)